I’ve been on Facebook since 2006 and Twitter since 2009. I decidedly don’t quit social networks because I decide this or that moderation policy isn’t leaning in my political direction. But, as of a week ago, I joined the push for a relatively new alternative social network, Mastodon, and I hope you will too.

Since the mid-2000’s, social media has been somewhat stagnant. Sure, we have seen the younger crowd go from Instagram to Snapchat to TikTok, but there have been essentially two fixed social media pillars, Facebook and Twitter, if you really want to be able to reach everyone.

Want to share photos and memes and rants with most of your friends and family? Facebook is the place. Want to get cutting edge news and such? Twitter is unsurpassed.

Somehow a few years ago, though, it suddenly became political to use Facebook and Twitter. When the dynamic duo cracked down on contrarian COVID positions and, later, dubious election claims, many on the Right said they were going to flee to Parlor or MeWe, or, later still, President Trump’s Truth Social. The same song, different chorus played when Elon Musk announced he was buying Twitter, only this time with those on the Left being thrown into a panic at the sheer terror that @realDonaldTrump might rise to tweet again.

As much as I have worried about deplatforming, the whole “I’m packing up and going to a new social network more likeminded to me” tact seemed ridiculous. I hope most of us still have friends outside of our ideological silos. Right? Please tell me I’m right on that. Surely ideologically fixed networks will never be a particularly good solution. Sure, it might be an enjoyable echo chamber for a time, but what about when you want to share photos with your family and not everyone votes the same way you do?

Despite the loud trumpets about leaving Big Social, little of this exodus really panned out. Networks like MeWe seem largely like ghost towns, reminding me a lot of the early competitors to Facebook that lacked traction.

If anything, with Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter last year, I felt a slight increase in optimism that Big Social would improve. Musk does not fit neatly into partisan boxes, so I hoped his vision of a “freer” platform would not be one sided. He wouldn’t just stop deplatforming one side in order to deplatform the other (which, frankly, is what most people seem to be hungering for).

For those of us who believe what Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote in 1927 that the best solution for bad speech is “more speech, not enforced silence,” Musk offered — despite his erratic style — a helping of common sense.

Twitter is, on some levels, headed in the right direction at this point. The “Twitter Files” reports have illumined some of the problems behind the scenes in the past, bringing much needed transparency. Protections against the vilest speech continue to exist, but the social network that functions as the “public townhall” has gotten lighter handed when moderation isn’t absolutely necessary. More speech combats bad speech.

So, what about this Mastodon thingy? Given my general stand against alternative social networks I just outlined and my appreciation for Musk, why would I suddenly find myself advocating for the network many on the Left have gone to in their hasty departure from a Tesla-tainted Twitter?

While I like many of the changes to Twitter, and respect Musk’s perfect right to do everything he is doing, his erratic side is a reminder of a different kind of problem: centralization. My argument has long been that we have become too dependent on centralized social media.

Do you really want to build your network of friends or audience for publishing or connection with customers on a service that one day decides to start banning people for the audacity of linking to something they posted on another social media network? A network that kills off third party tools that had helped people post to it for much of its existence without even explaining the decision until days later? A network that abruptly shuts down the free programming tools (APIs) that helped make it better tie into a whole world of other services and added rich content to it over the years?

In each of these cases, Musk and Twitter have backed off to some degree after making an initial extreme decision, but even if it totally reversed just those three biggest follies, the instability of its shifting sands approach has surely done lasting damage. For a platform where most of its unique features — even things like retweets — started out as user built innovations, those last two decisions are absolutely deadly. No one in their right mind would invest in a major Twitter programming initiative when it has shown such an unpredictability about policy changes.

Twitter as a platform will stagnate because of this, even if it stays busy with people posting for the foreseeable future.

And so, I’ve seen not just my most Left-leaning friends and follows, but many of my most interesting tech savvy Twitter follows start to yearn for a more stable ground. The very sort of thing I argued about in the piece where I asserted the need to return to the blogosphere two years ago.

They’ve landed on Mastodon. Given the pull to ideological silos, is this just the Left’s equivalent of the Right joining Truth Social and Parler? To be sure, Mastodon leans Left right now, but its unique design means it doesn’t need to lean one way or another. And, whatever the reason that motivated people to jump the Twitter ship, their impulse to go to Mastodon makes an awful lot of sense over other alternatives.

The best way to understand Mastodon is to rewind a few decades. When many of us first came online, you could primarily communicate with other people using the same provider, whether it was a “BBS” or an online service like Prodigy. When I was on Prodigy and some friends were on the new “upstart” of AOL, I couldn’t necessarily reach them.

That changed thanks to the Internet’s broad availability. The foundation of the Internet is decentralized. You may have a Gmail e-mail address and a friend may have an iCloud address, but if you know that person’s address, you can communicate across services. Likewise, when we browse the web. Thankfully, I don’t browse the “Spectrum Internet” while others browse the “AT&T Internet.”

Yet, we’ve allowed ourselves to be drawn into something akin to the bad old days of those proprietary online services with social media. If you want to interact with people on Facebook, you must be a Facebook produc — ahem, I mean — user. Likewise, if you want to take part in the Twittersphere, you are going to have to work with Twitter, Inc.

This was a huge boon to ease of use, but a huge regression from the blogosphere of the early 2000’s where anyone could host their own blog. We managed to comment, connect and grow “networks” then, but without any central power having control over it. Back then, no one could just “deplatform” users they didn’t agree with or, for that matter, go wild and turn off a bunch of core functionality.

Yet we ceded all that to these few, now incredibly powerful companies that — in one of the few points of agreement between them — both Left and Right agree are too powerful and too intrusive.

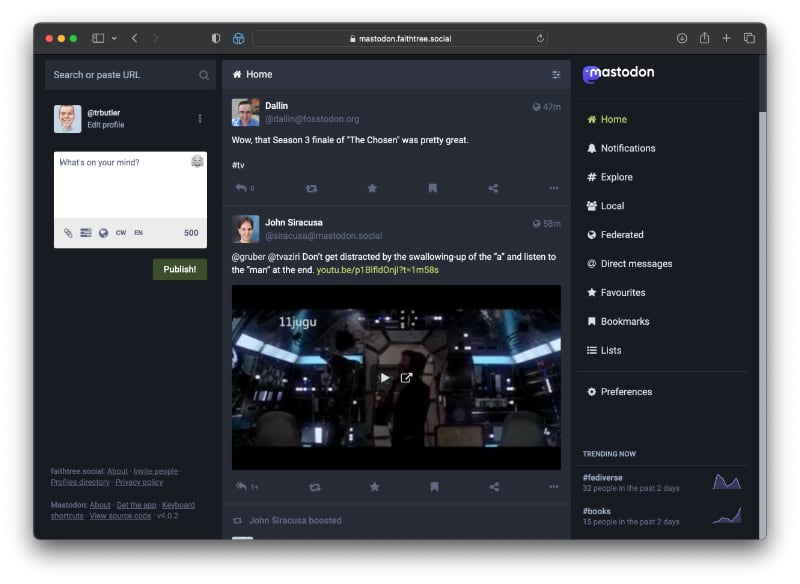

Mastodon offers a return to the earlier Internet, but with a decidedly modern twist. Like we expect from Twitter or Facebook, it has a central timeline that lets you know what your friends, celebrity follows or anyone in-between has to say. You can easily post photos and videos from your mobile devices.

It is a genuine, modern social network.

But there’s no central Mastodon company that rules the thing. Mastodon is open source software and anyone — including me! — who wants to can setup an “instance.” (The equivalent of your tech savvy friend who has his own domain name — something dot com — for e-mail.) These instances are separate, but just like e-mail, can communicate with each other. This interconnection between Mastodon, and even other tools beyond Mastodon itself, is known as “the Fediverse.”

One can find a group of like-minded people on a particular instance (the one I setup is for folks involved with the church and ministry I lead, for example) or find an instance that is open to anyone who wants to sign up. Some are free, some have a cost to join. But all of them can communicate with each other, so it isn’t about picking which ideological silo seems best and only talking with those people.

This decentralized arrangement means neither a billionaire libertarian-leaning space ace nor a billionaire metaverse obsessed leftist can upend your online home. At worst, if an instance proves itself particularly obnoxious, other instances can choose not to talk to it any longer, but that is something decided on an individual instance level. Decentralization is beautiful.

(If a user finds an instance no longer desirable to be on, he or she can use the built in tools to migrate to a different, better suited one, too, bringing all his or her followers along for the ride. That’s like changing e-mail addresses but not having to worry about telling everyone to update their address books!)

This idea of returning control to users (or at least administrators overseeing a relatively small cluster of users on a given instance) is a compelling win for healthy, vibrant free speech. Decentralization also means we step outside of Big Social’s attempts to surveil us and exploit our data as something to sell.

After years of sitting on the periphery, Mastodon appears poised to bring these advantages to normal folks like you and me. Many app developers just banished from Twitter — the ones who helped make Twitter easy and fun to post to — have turned their genius efforts to making Mastodon easier to use. It does have some friction — say in trying to find your friends or following people from other instances — that isn’t hard to overcome, but improved tools are welcome to help bring Mastodon up to the ease of use of Twitter and Facebook.

Speaking of finding people on the network, numerous significant organizations have started hosting a presence on Mastodon, unlike most other alternative social networks. Many of my favorite indie software development companies are now on Mastodon and several figures from major corporations like Apple and Microsoft have likewise appeared. The Washington Post has started verifying its journalists that are on the network, providing a step toward legacy media legitimacy, while most of the major tech media is at least dipping its toes into a Mastodon presence. Things are filling in.

Mastodon appears on the cusp of “critical mass,” where it will be a necessary tool for those who want to be in the loop in different areas of thought, just like Twitter has been. And yet, for now at least, it has a small town feel that reminds me of that blogosphere of old. People I follow, many of whom I’ve just met while playing with it, seem less uptight and less “flame-y.” Mastodon users — ideologically similar or not — exhibit a helpfulness to newcomers and a sense of shared eagerness for what is to come.

I reliably see what the people I follow say, too, because the infernal algorithms of social media that are focused on addicting us to scrolling, as opposed to showing us what we consciously want to see, are notably missing. The Mastodon timeline shows me what I asked it to show me.

Will Mastodon keep that old timey attitude as it grows? Will algorithm-free news feeds prove too inefficient when one follows hundreds of one’s “friends” like we do on Big Social? I’m not sure. But so far, I can say I like what I see.

Even if Mastodon eventually feels a bit more like Facebook or Twitter, it has one huge advantage: it is not and will not be centralized. The user is in control.

That’s better for us all, so even if you’re like me and not eager to burn “the Bird App,” I hope you’ll add a fuzzy elephant app alongside it and join me on the Fediverse. You can follow me at @trbutler@faithtree.social and follow OFB itself @ofb@faithtree.social.

A decentralized Internet is a better place and a decentralized Internet with you is better still.

Timothy R. Butler is Editor-in-Chief of Open for Business. He also serves as a pastor at Little Hills Church and FaithTree Christian Fellowship.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation