My congregation got a preview of a new show set in Biblical times. By the look of the clips, it could be a spinoff of The Chosen. There’s just one peculiar difference that makes all the difference, for good or ill.

It wasn’t the cast. They sported the same high-quality costuming and performed in scenes every bit as detailed as that popular Biblical episodic drama series, Amazon’s similarly formatted House of David or films like The Passion of the Christ. Nor the cinematography, which hinted at a big-budget production.

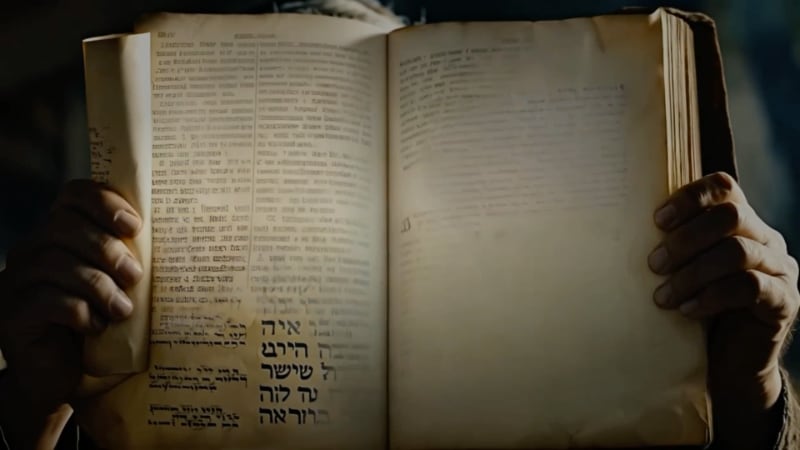

The snippets we showed drew from the Gospel of John, showing several future events Jesus refers to. Being a good iconoclast, mind you, we didn’t air any scenes that actually show Jesus himself, but rather a man being healed, a Pharisee contemplating and a bit of judgment coming from no less a teacher of the law than Moses himself. Just like those other productions, none of it was kitschy.

None of this sounds particularly notable — after all, every time some Biblical film project does well, Hollywood suddenly rediscovers religion and tries to duplicate it to death. The clips usually look impressive, even if the storytelling is “meh” when viewed as a whole.

But this one didn’t come from Hollywood.

Like many churches today, we open sermons with a video “bumper” that helps frame things. In this case, a series on John 5, the portrayed scenes are ones Jesus describes in that chapter.

While such videos themselves aren’t unusual, showing Hollywood-grade enactments has typically involved incredibly expensive licensing. Expensive enough that a small church like mine just has to opt not to show the clips at all. There are far more urgent needs for the money we do have.

As a pastor with a bent for technological creativity, I took the budgetary limitations of our size as an excuse to produce the opening videos myself. That did mean eschewing anything like what I described above. Instead, I opted for what I could draw from my own photographic abilities — everyday life scenes or sweeping nature panoramas — to capture a series’ mood and theme free of burdensome licensing.

And free from casting and set design. I’m a pastor, not a producer, Jim.

So what changed this time? It comes down to that peculiar difference from The Chosen. What was it? The people starring in it don’t exist.

Yes, the video was produced using Veo-3, the Google AI video tool that is at the present leading edge of generative production.

I’ve utilized AI bits for past bumper videos, dabbling with the surreal AI morphing videos of tools such as Deforum’s Stable Diffusion variant. They created videos with a style so unmistakable it had a brief cultural moment at the dawn of generative AI, even influencing a Marvel miniseries’s opening credit design. But that unmistakable quality was that of other.

The last two videos I put together are “other” for how much they are decidedly not other. Early generative AI “prompts” felt akin to computer programming with awkward stilted phrases adjacent to, but unlike, human language. The results were likewise clearly of the digital world.

No longer. Instead, I put on the hat I had previously toted as an amateur playwright and composed what amounted to a mini-play. The photorealistic output, like the more organic input, appears to belong in our world, not the computer’s.

I’m sure some megachurches with soundstages — yes, that’s a thing — have in their archives scripts just like the one I wrote, crafted for videos just like the one we showed. Five years ago, if you saw my script and the result, you’d have assumed that I had gained access to such a resource.

A script being turned into a filmed drama is incredibly natural. Post-production — so far — even looks like it traditionally would have. I spliced different takes, edited bits to make sure to get the right points across and so on. Yet, it is uncanny to see it come alive without it ever being, well, live.

I’ve written extensively on AI over the past few years and I still struggle with precisely how to make sense of some of this. One could fault me for using Veo-3 and depriving actors, scene construction crews, gaffers and everyone else of a job.

If I pastored a big church with a big budget, that might even be fair. As it is, no actors were harmed in the making of those videos because a small church like mine could never hire them anyway. The few bucks in “compute credits” necessary to run Veo come out of my own pocket and my pockets are nowhere near that deep.

Of course, if I can do it, larger-pocketed churches and every other sort of organization will too (and already are). That’s the part that leaves me conflicted.

While I don’t see the same ethical dilemma in taking a script I wrote and having AI enact it as I do in having AI research and write a study of health policy or, for that matter, a sermon, its capabilities are disquieting regardless of application. I feel a sadness thinking of a day when those gifted with acting and creating cinematic art might get largely passed over for a computer processor.

Admittedly, some might accuse me of special pleading when I assert ethical issues over AI producing my vocational work of preaching, but don’t here. Yet, there is a distinction between a computer rendering a result and a computer replacing the human mind in research, generally, as with the aforementioned health report. And when we say that research should be mediated through prayer before God in sermons? That seems even more problematic to replace with a machine, because the machine ain’t praying.

But where is the line? What if I’d only told the AI in broad strokes my envisioned Biblical scenes and let it write the script too? Is there a prayerful and theologically reflective aspect to my layout of the video before a sermon that I’d be skipping over? Oh, yes, very much so. Of course, an actor might interject that he or she researches and prays before performing, too.

So, where is the line? Technology is progressing much faster than our ethical understanding of what needs human touch and what just could have it.

I’d like to think the existence of Veo-3 has been a net positive in this particular case. The videos I put together — AI or not — aren’t just for show. I craft them to be a visual overview of a multi-week series, one that previews the weeks ahead and, by its repetition each week, becomes a recap of what we’ve already covered. Sure, I could go without, but I’m thankful for gaining another tool to convey truth via a visual medium.

And no job was replaced for me to have it. Actors’ protestations are moot if I never had the budget to hire them and roll cameras anyway. Nothing was lost in this case. AI didn’t replace a job or even let me get lazy on mine. Instead, it enabled me to do something extra I’d otherwise have been unable to do within my means.

Industrialization, the printing press and the like opened up access to things previously reachable only to the very wealthy. But the common person’s gain came at the cost of hurting the people whose jobs were replaced. AI tools are on the same path, with the same type of benefits and the same wreckage. Even where it is for the best that it replace certain jobs, the pain is real.

The best we can hope to do is leverage it fully where it replaces no one (as with my video) and use it judiciously where it does. Most of all, we need to seek the best way to add human contributions as machines take over what was once our exclusive domain.

The solution to industrialization was not Luddism. Neither will a remixed form solve the present, unstoppable advancement of AI. No attempt to save jobs for the mere sake of saving jobs succeeds in the long term.

But we must use wisdom to watch for those uniquely human contributions that AI replacements can’t provide. That starts with asking the very question of what is right.

Ethical discernment — whether concerning AI or any other aspect of life — is a uniquely human task. One we must never outsource to a mere algorithm.

Timothy R. Butler is Editor-in-Chief of Open for Business. He also serves as a pastor at Little Hills Church and FaithTree Christian Fellowship.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation